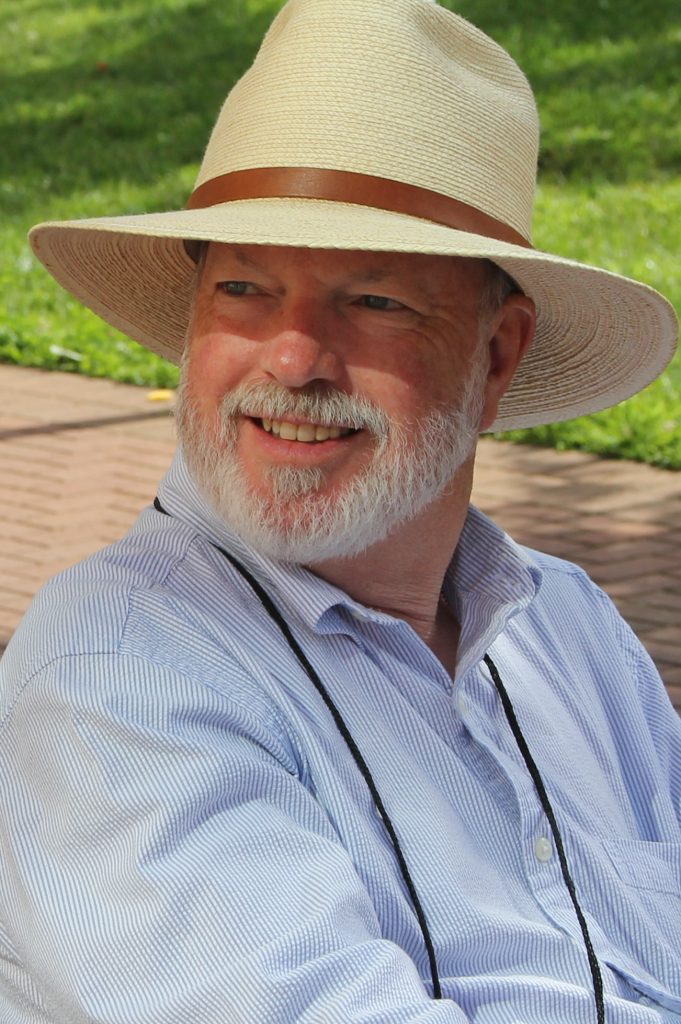

With more than twenty books and numerous articles and short stories published since the 1980s, BRENT BILL has learned a thing or three about writing. His book titles include Hope and Witness in Dangerous Times, Beauty, Truth, Life, and Love, Life Lessons from a Bad Quaker, and the forthcoming Amity: Short Stories from the Heartland. He’s a writing coach, editor, photographer, and popular writing retreat leader. Brent lives on Ploughshares Farm – fifty acres of Indiana farmland being returned to native hardwood forests and warm season prairie grasses. Visit his website at brentbill.com.

With more than twenty books and numerous articles and short stories published since the 1980s, BRENT BILL has learned a thing or three about writing. His book titles include Hope and Witness in Dangerous Times, Beauty, Truth, Life, and Love, Life Lessons from a Bad Quaker, and the forthcoming Amity: Short Stories from the Heartland. He’s a writing coach, editor, photographer, and popular writing retreat leader. Brent lives on Ploughshares Farm – fifty acres of Indiana farmland being returned to native hardwood forests and warm season prairie grasses. Visit his website at brentbill.com.

Brent will teach the session “Writing From the Heart.” And he will evaluate manuscripts as part of the Manuscript Evaluation Team.

In this interview, Brent Bill offers wise perspectives on the writing process and writing life–including best practices for attending a conference!

MWW: Can you compare the process you go through in writing a short story compared to a non-fiction book?

BB: The actual writing part is pretty much the same, since my non-fiction books, such as Holy Silence and Life Lessons from a Bad Quaker are pretty dependent upon story telling. The process I go through in writing varies only in when I’m deciding what medium works best for what I want to do. By that I mean, in my non-fiction books, people are often reading for information. Entertainment comes second. They want to enjoy it, but they’re reading to learn something or explore an idea. In my fiction, they’re reading to be entertained, to get engrossed in a well told tale. The stories in my non-fiction books are shorter whereas in my short stories, even though they’re short, there’s the opportunity to really get into the meat of the story I’m telling. I get to spend time with the characters and get to know them in a way I don’t in my non-fiction since those are stories about “real” people. So I spend more time pre-writing – thinking about these people, imagining how they’re going to act and speak. What they look like. All the things that hopefully bring a character to life for the reader.

MWW: As someone who leads writing retreats, you’ll have a special insight into this—How can a writer get the most out of an experience like MWW?

BB: I think there are a number of ways. First, even if you’re an introvert like me, meet people. You’re going to have a great opportunity to meet fellow writers, editors, agents, and other folks. For instance, I met two of my editors and my agent at a writing conference. Some of these contacts will become friends and besides you’ll learn a lot from them, even in informal settings like over meals and on break.

Second, take a workshop that may be outside your comfort zone or area of interest. At one of my first Midwest Writers Workshop, I, as a writer of non-fiction back then, took a poetry course. I didn’t have any intention of ever writing poetry (and I still don’t!) but I learned so much about the use of language and imagery in that workshop. It alone was worth the price of admission.

Finally, relax and enjoy the experience. You’re among writing friends, whether you know everybody or anybody. Have a good time!

MWW: At what point did you consider yourself a writer? Do you think there are special qualifications for that title?

BB: I think the first time I considered myself a writer, though I’d been writing all kinds of things for a long time, was when I started having pieces published on a regular basis. Then, when my first book came out, I really felt like a writer. It was then, though I had a full-time job to “pay the freight,” I realized that writing is my vocation and that’s who I am. A writer.

So far as special qualifications go, I used to think so. As a kid who spent an inordinate amount of time in the Hilltonia Branch of the Columbus (Ohio) Public Library, I was reading all the time. I thought writers had to be the smartest, most amazing people ever. I still think that about some writers I know, but once I became one I realized the special qualification was wanting to be a writer and being willing to learn the craft of writing because there was something (or some things) I wanted to say. I’m not sure I have any natural talent as a writer, but I really wanted to become one so I learned to write, rewrite, rewrite, and rewrite. So perseverance is a special quality. Along with the ability to read a rejection slip and think, “I’ll show you,” and work on the piece and send it out again!

MWW: When a writer has not reached a hard conclusion by the end of their memoir, how can they still make the work satisfying for the reader—or, perhaps, is the work in fact more compelling if it leaves certain strings untied?

MWW: When a writer has not reached a hard conclusion by the end of their memoir, how can they still make the work satisfying for the reader—or, perhaps, is the work in fact more compelling if it leaves certain strings untied?

BB: I’ve never written a true memoir, though many of my readers think a number of my books are in fact spiritual memoirs. I read a number of memoirs and would say united strings make them more compelling. I don’t like being told what the point is – in memoir, fiction, or non-fiction. I like the joy of discovery and surprise. And that’s what I try to do in my writing.

In my forthcoming collection of short stories, Amity: Stories from the Heartland, there are no morals to the story. Well, there are, but not ones I telegraph. I think the moral is in the mind of the reader, whatever she or he makes of them. But mostly, I just want them to enjoy them and I think enjoyment is easier if the touch is lighter and left to the reader’s imagination.

*Though “Amity” won’t be officially released until November, Brent will have copies available for sale to attendees at MWW! Check out this tip sheet for more info.

MWW: Talk about a time when working on a piece changed you fundamentally.

BB: That probably came when I was writing Holy Silence: The Gift of Quaker Spirituality almost twenty years ago. I had already had eight books published by then. So, I was a technically good writer. I could write to deadline and word length. My books sold well. But when I submitted my first draft to my editor, Lil Copan, she said three things that changed me – and the book.

The first was, “You’re a good writer.” So I beamed inside. Then she said, “Do you want to be great one?” Wow. That cut to the heart of the matter. So of course I said yes and began to learn from her wise editing about how to make my writing stronger, clearer, and more compelling.

The second was, “You almost reveal yourself. Every time the reader thinks she’s going to get to know you, you pull back. Take a chance and show yourself.” By that she meant I was playing it safe. Writing at distance. Emotional detachment. So I began to write honestly and share my feelings more in what I was writing about. Since I’ve always relied on stories in my work, I started telling more of the whole story – not just the safe stuff. That was scary, but rewarding both for me and my readers.

The third was, “I know you’re a preacher (I was a pastor back then), but cut it out.” By that she meant that I’d too often adopt a tone that was unwelcoming and didactic. So, I learned to tell the story and let it do its own work. And that has work in both fiction and non-fiction.

MWW: Your turn! What question do you wish that someone would ask you about writing, but nobody has? Write it out and answer it!